When I was working on my Masters in data science, one of the projects I did was to create an algorithm that would take an intended use statement for a medical device and predict whether FDA would require a clinical trial. It worked fairly well, with accuracy of about 95%.

Since that’s a dynamic algorithm in which the user inputs an intended use statement and gets a prediction of FDA’s decision, I wanted to go about a similar task this month: create a static word cloud to show what words are most associated with intended use statements where FDA has required a clinical trial. At least in theory, this static representation might give you a sense of words in an intended use statement that are more likely to push your device toward a clinical trial.

Results

In this word cloud, the size of the word reflects its frequency in intended use statements associated with devices where FDA required a clinical trial.

Methodology

I started with FDA’s 510(k) database, and my first task was to extract the intended use statements from the PDF documents on FDA’s website. That requires a lot of work, but I won’t bore you with the details here. It involves first reading all the 510(k) summary pdfs available through FDA’s website, and then extracting the intended use statements from those PDFs. Someday I hope FDA brings a bit of structure to the 510(k) summaries. Even a little bit of structure would help researchers tremendously. It also would bring some consistency to intended use statements, where compliance with the regulation varies widely.

The next task was to identify those 510(k)s where a clinical trial was conducted. That’s both easy and hard. The easy part is going through FDA’s database on its website – this is not in openFDA – in identifying all those 510(k)s where there is an NCT number reflecting a clinical trial registered on clinicaltrials.gov. I wish they would include that information in openFDA, but they don't. OpenFDA databases are years behind the databases on FDA's own website.

I was tempted to stop there, but I know full well that a lot of companies conduct clinical trials to submit with their 510(k)s that are not registered on clinicaltrials.gov, in part because not all trials need to be. As a result, my next step was to look at the 510(k) summaries, and through searching for certain keywords that are almost exclusively associated with clinical trials, identify additional 510(k)s were clinical trials were part of the mix.

At this juncture, I had a list of all 510(k)s, a list of all 510(k)s that involve a clinical trial, and the intended use statements for all 510(k)s. In round numbers, doing this in April 2024 and using a data set that begins in January of 2001, I had about 46,000 510(k)s where there was no clinical trial, and about 4000 where there was. In other words, for that data set, only about 8% of 510(k)s were associated with clinical trials. I suspect that is understated, but I also know that in the earlier years in particular full blown clinical trials were not that common for 510(k)s.

My goal, as I said above, is to identify those words most frequently associated with devices that involved a clinical trial as a part of the 510(k) process. I decided that the best way to represent this mathematically was to calculate 1) the frequency of all words used in intended use statements where a clinical trial is involved and subtract 2) the frequencies for all those words used in intended statements were clinical trial is not involved. So if a word is more frequently in a clinical trial intended use statement than not in an intended use statement where there was no clinical trial, that would be a positive number. I thus only cared about positive numbers. A negative number would be associated with intended use statements that more often do not involve a clinical trial.

Mechanically, I used the nltk library to do tokenization, followed by calculating frequency. I focused on the 1000 most frequent words. I removed many stop words because I consider them uninformative. In addition to the typical stop words, I removed words like “intended”, “human”, “patients”, “results”, “clinical”, “healthcare”, “device”, and “indicated”.

So that’s how I ended up with the words for the word cloud. The depiction represents the degree to which words are more frequent in intended use statements for devices with clinical trials, as compared to intended use statements for devices that do not involve a clinical trial.

Context

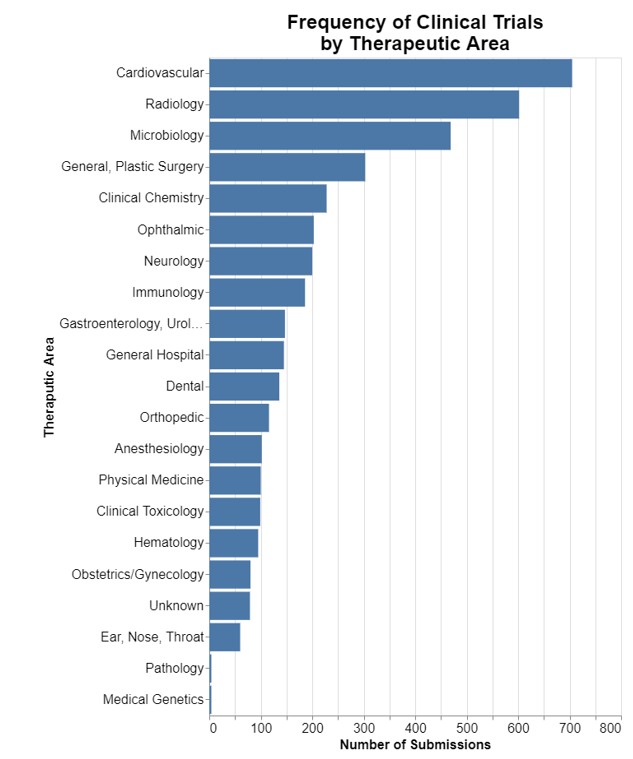

It’s hard to simply interpret the word cloud without a bit of context. As a result, for context, but also to frankly evaluate how well or not well I did at identifying submissions involving clinical trials, I thought I would depict the therapeutic areas in which clinical trials are most common. The following chart indicates the frequency of clinical trials by therapeutic area using the techniques I described above for selecting submissions that involve clinical trials.

The chart jives with my understanding of FDA expectations for clinical trials from submissions I’ve observed, but let me know if it departs from your experience.

Interpretation

When I look at the word cloud, the thing that hits me between the eyes is the preponderance of words commonly associated with in vitro diagnostics. In fact, it’s as if all the most common words are probably related to IVD’s.

While certainly it's true that IVD's do frequently require clinical trials and that overall that probably is a macro trend, that’s at odds with the high frequency of clinical trials for cardiovascular devices. An explanation I can think of is that there is common vocabulary regarding a wide variety of IVD’s, whereas individual cardiovascular devices frequently have their own specialized words. Where nearly any IVD might be referred to as a test or an assay, cardiovascular devices like pacemakers and defibrillators have their own special labels.

It's also true that there are many medical specialty categories related to IVD’s including microbiology, clinical chemistry, immunology, clinical toxicology, and hematology, and if you add all of those IVD categories up, the total is the most predominant area for clinical trials.

I do see some cardiovascular device words such as ECG and some radiology terms such as images and x-rays, but again they are nowhere near as prominent as the IVD vocabulary.

On the whole, this analysis suggests that if you use words that describe your product as a laboratory test, it is more likely to be associated with a clinical trial in a 510(k) submission.

Conclusion

There are, of course, no magic words that automatically mean a clinical trial is required. But it is disproportionately likely if you’re using words that in effect describe a laboratory test, a clinical trial may well be required. The most common words are probably the least interesting, simply because we could all have probably predicted those. I find some of the mid-size words to be more interesting. For example, I'm fascinated by the frequency of the word “software.” It's also interesting to me that the word “influenza” is prominent. I would not have guessed that a disease that is so common is associated with devices that require a clinical trial. I'm also surprised to see the word “monitoring” so prominently listed, as often we consider monitoring to be a pretty low risk task. The word “respiratory” likewise surprises me just because I personally haven't seen that many respiratory clinical trials. I hope you might find insight in some of the medium frequency words that maybe aren't obvious.

* * * *

The Unpacking Averages® blog series digs into FDA’s data on the regulation of medical products, going deeper than the published averages. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s). Subscribe to this blog for email notifications.